In those wonderful days prior to Covid-19, tourism vied with dairy as New Zealand’s biggest export industry. In 2019, tourism comprised 18.65% of New Zealand ‘exports’ to the rest of the world while dairy contributed 18.81%. Other biggies are meat and edible offal (9.38%), wood (5.85%), fruit and nuts (3.98%), and cereals (2.67%). What differentiates tourism from these other big earners of offshore revenue for New Zealand?

- Dairy: research to support this industry is conducted by DairyNZ, the Fonterra Research and Development Centre, the Dairy Research Institute, the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI), and others.

- Meat: research to support this industry is conducted by the Meat Industry Research Institute of New Zealand (a division of AgResearch), Beef+Lamb New Zealand, the Meat Industry Association, MPI, and others.

- Wood: research to support this industry is conducted by Scion, the Wood Technology Research Centre at the University of Canterbury, the New Zealand Farm Forestry Association, and others.

- Fruit and nuts: research to support this industry is conducted by Plant & Food Research, MPI, Zespri, and others.

- Tourism: research to support this industry is conducted by … hmm, well, nobody actually.

Four out of five of New Zealand’s top export earners have significant research support, some with large Crown Research Institutes (CRIs) conducting research to help those industries remain innovative, internationally competitive, and responsive to the imperative to become net carbon zero by 2050. If I am a tourism operator and I want to conduct some research on how to lift the quality or sophistication of what I am providing, where do I apply for that funding? Alternatively, what government-funded CRI do I have at my beck-and-call to conduct that research for me? Who is funded to help me transition to a net carbon zero service?

The question I would like to pose in this monthly piece, is this: Given that tourism is either New Zealand’s biggest, or close to biggest, export earner, why is there no massive investment in tourism research to maintain this vital sector of New Zealand’s export economy? I don’t know the answer, but I have been wondering what can be done about that.

Here is an idea and, like many of my ideas, I don’t know if it’s a good one or a bad one. I need you to tell me (email your thoughts to me at greg@bodekerscientific.com). Here it is:

Since 1 July 2019, most international visitors to New Zealand have been charged the International Visitor Conservation and Tourism Levy (IVL) of $35. Half of the funds collected go to the Department of Conservation (DoC) for (i) biodiversity (35-40% of the IVL) and (ii) responding to visitor pressure on conservation and the environment (10-15%). The other half goes to (i) tourism strategic infrastructure (40-45%) and (ii) tourism system capability (5-10%). None of it goes to tourism research and development (R&D) and none of it is available to help the tourism sector transition to being net carbon zero.

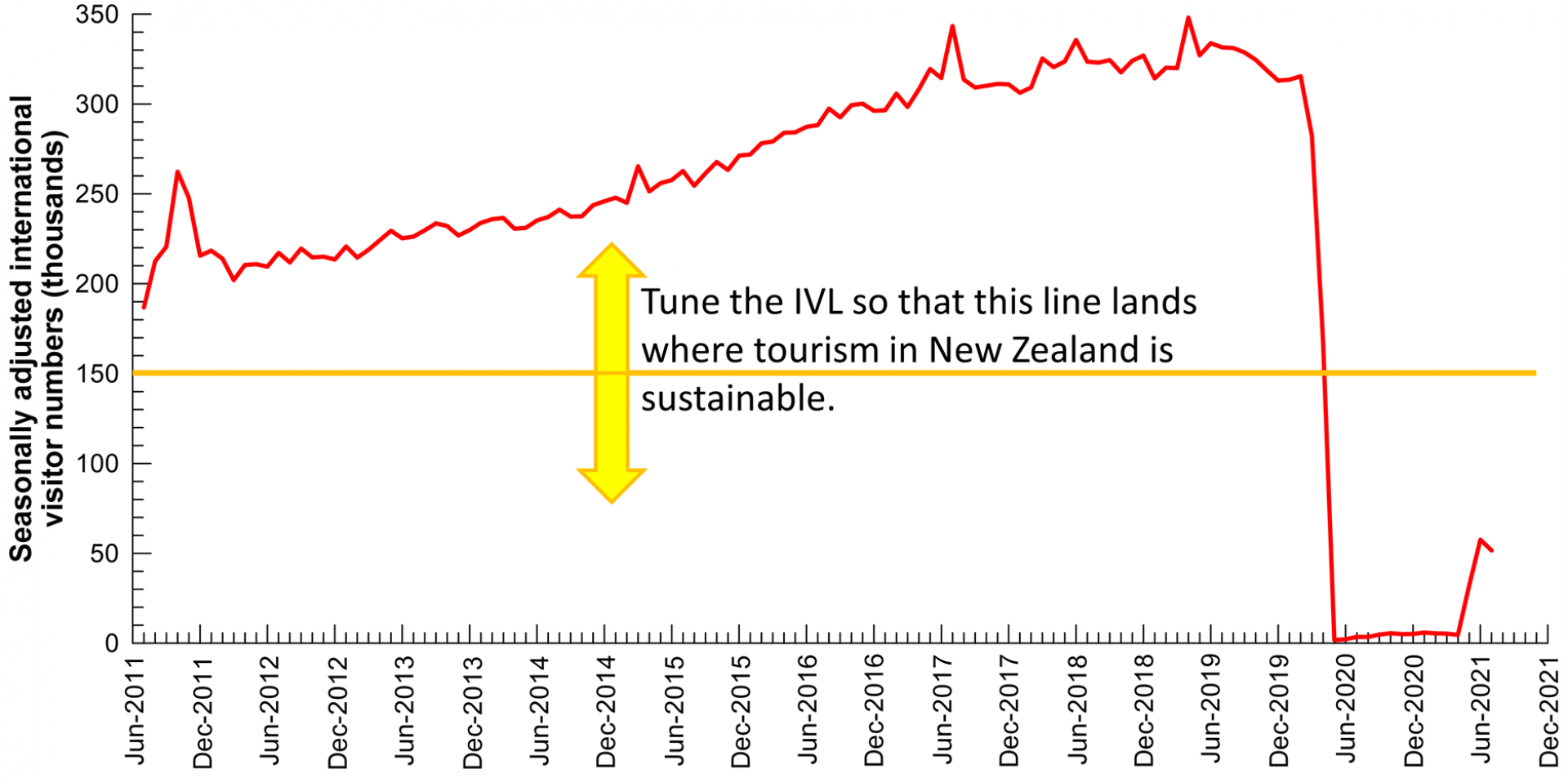

What if we increased the IVL from $35/tourist to $350/tourist? Yes, tens time higher! That may halve the number of tourists coming to New Zealand (a complete guess on my part), noting that the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment observed ‘respective cabinet papers and regulatory impact statements reveal that these levies were deliberately set at modest levels to avoid any chilling effect on demand’.

Seasonally adjusted overseas visitor arrivals peaked at 348,100 in May 2019. That would have generated $12.18M/month, of which $6.09M would have gone to DoC and the other half to building toilets at freedom camping spots etc.. Now, if we go for an IVL of $350, halve the number of tourists, and still give DoC their $6M and the infrastructure developers their $6M, that leaves a little less than $50M, each month, to do something cool. So, what are we going to use our $600M each year? We could:

- Pay tourism service providers to collect data on their carbon footprint and to use those data to chart their transition to being net carbon zero as part of their value proposition to their clients. Expecting providers to do that at their own cost is unreasonable, especially in an industry with slim margins and the challenges of digging their way out of the covid hole.

- Conduct research that will allow New Zealand’s tourism sector to transition to net carbon zero, and to a values-based model where we determine the kinds of experiences we want tourists to have, and the kinds of outcomes we want for New Zealand. As described by the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, conducting such research would need to delve into the ‘cold hard realities’ of pricing, rationing, access, and the need to internalise all the environmental externalities associated with noise, crowding and greenhouse gas emissions.

- Develop a fully funded carbon intensity accreditation system that would make it possible for tourism service providers to reliably promote their carbon credentials.

- Buy lots of chocolate. Afterall, you shouldn’t waste all of that $600M

Spot the effects of Covid-19? Essentially, we set the IVL so that the number of tourists coming into New Zealand (i) doesn’t overwhelm the capacity of our infrastructure and ecosystems, (ii) generates sufficient revenue to achieve the goals outlined above, and (iii) permits a system that supports our values while being commercially sustainable. Maybe $350 is too high. I don’t know. Let me know what you think.

Related Stories

-

Batteries and storing energy

“Nothing is more dangerous than an idea when it’s the only one we have” as Émile-Auguste Chartier once said. This quote springs to mind when I think of the Lake Onslow scheme. For those who may not know about the Lake Onslow scheme, the idea is to convert Lake Onslow, which sits in a shallow depression in the hills between Roxburgh and Middlemarch, into a giant battery. Importantly, Lake Onslow is around 685m above sea level while the Clutha River downstream from Roxburgh is at around 94m above sea level. That’s a 591m difference (see, those three years of maths at university are paying off).

Read more about Batteries and storing energy -

Extreme events and climate change

Consider the Paris Agreement where countries around the world have agreed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions with the goal of limiting global warming to well below 2°C, preferably to 1.5°C, compared to pre-industrial levels. Some people think “Who cares? It was 2°C warmer today than it was yesterday. 2°C is peanuts!”. Or consider sea-level rise. That could be around 3mm/year along the coast of Otago. That’s 3cm in a decade. Again peanuts, right? A wave could be 5 metres high so why are we worried about a 3cm rise over a decade?

Read more about Extreme events and climate change -

The Central Otago Destination Management Plan and Climate Change

CODC recently released its Destination Management Plan (DMP). I have read it and I think it’s excellent – and painful. Why painful? Because change is painful and this DMP highlights many changes to the way we do things that will be required. In this piece, I am going to share my thoughts on those aspects of the required changes articulated in the DMP that relate to climate change and are directly relevant to tourism services providers. Climate change poses an existential threat to some of the values that underpin the DMP, in particular Mauri - pressures imposed by land and water use are already being exacerbated by climate change and will be more so in the future.

Read more about The Central Otago Destination Management Plan and Climate Change -

Wood-burners and climate change

I often get asked about whether using wood-burners for interior heating contributes to climate change. For the purposes of this article, let’s set aside the effects that the use of wood-burners have on out-door air quality. Smoke from using wood-burners contributes to poor air quality; you only need to walk around Alexandra on a cold winter’s night with a strong inversion layer to notice that. But that’s mostly a different issue to climate change – I say ‘mostly’ because the aerosols (smoke) from wood-burners, if anything, make a small contribution to cooling the climate by reflecting solar radiation back to space before it reaches the ground.

Read more about Wood-burners and climate change