The primary tool that New Zealand’s government is using to both impose a price on carbon and reduce our greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, is the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). The goal of the ETS is to support New Zealand in meeting its international obligations under the Paris Agreement, i.e., achieving a net carbon zero economy by 2050 and associated GHG emissions targets along the way. Remember that the goal of the Paris Agreement is to limit global warming to well below 2°C, preferably to 1.5°C, compared to pre-industrial levels.

All sectors of New Zealand's economy, apart from agriculture (now there’s a hot topic for me to write about next time!), pay for their emissions through the ETS. Businesses in the ETS are required to ‘surrender’ a New Zealand Emissions Unit (NZU) for every tonne of CO₂-equivalent they emit. What’s this ‘CO₂-equivalent’ business? To allow all GHGs to be lumped together and treated interchangeably, gases other than CO₂ are converted into a CO₂-equivalent (CO₂-e) using some scaling. Methane, for example, because it is 25 times more potent as a GHG compared to CO₂ (see my piece from last month), is multiplied by 25. So, if I emit say 50 tonnes of CO₂ and 5 tonnes of methane, my CO₂-e emission is 50+(25×5) which equals 175 tonnes. For that I would need to surrender 175 NZUs. Where can I get these NZUs? I can either:

1. Buy them at a government auction. These happen four times a year. Last year there were 19 million of these NZUs up for grabs at the quarterly auctions (plus an extra 7 million in the September auction, but we won’t get into that now). This year there are going to be 19.3 million, but then in subsequent years this falls to 18.6, 17.2, and 15.5 million NZUs.

2. Hope to be given some free NZUs by the government, e.g., maybe because I am a ‘Emissions Intensive Trade Exposed’ (EITE) business.

3. Buy some off an NZU generator. NZUs can be generated by way of carbon farming, i.e., growing trees and selling the resultant NZUs. One hectare of ten-year-old forest might earn anything from 8-24 NZUs/year, depending on the tree species. If sold at the current price of $68.50/NZU (see below), this would equate to around $550-$1650/hectare/year.

4. Buy some off someone who has previously bought NZUs and is holding onto them.

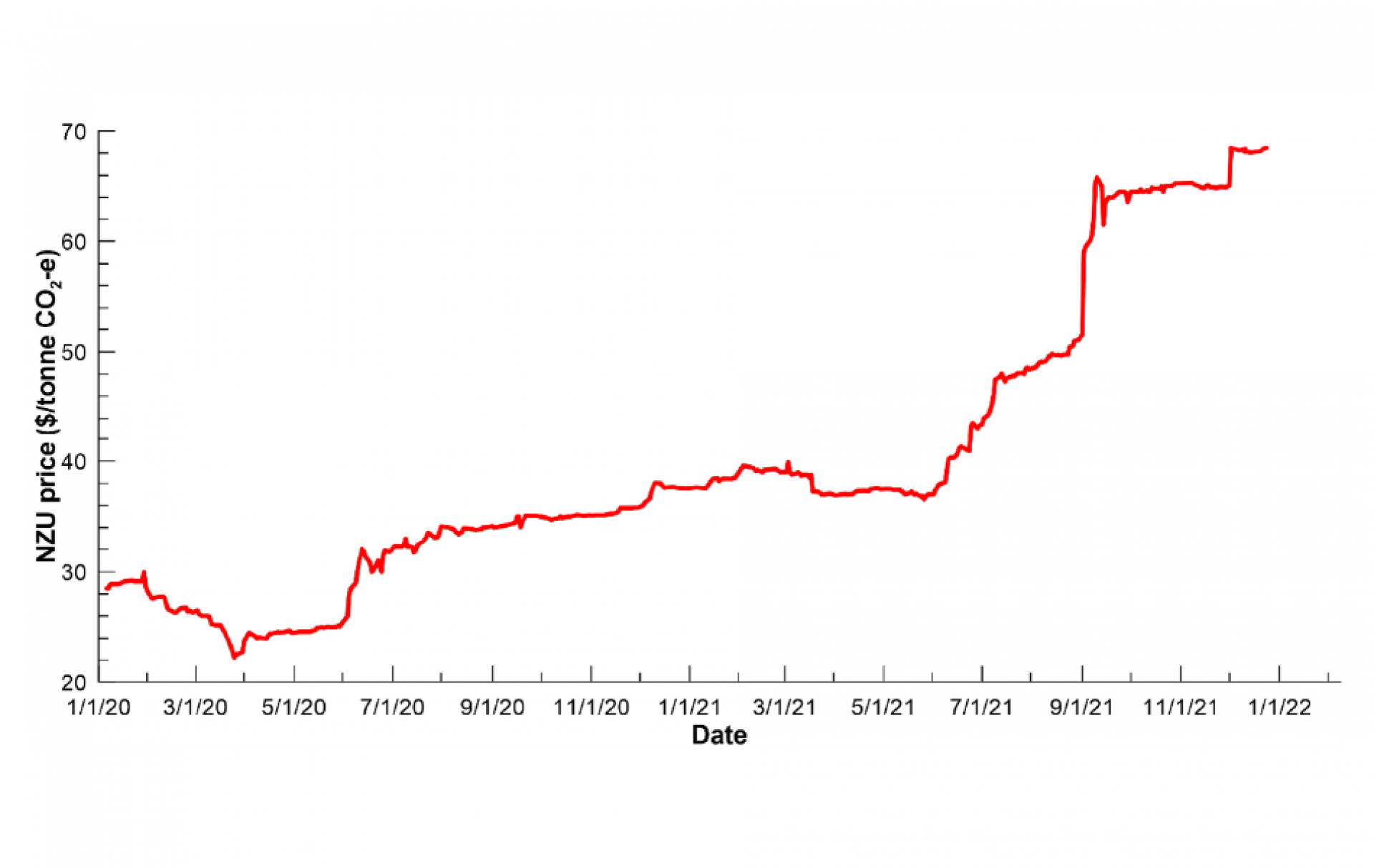

How is this market doing? Well, here is what has happened to the price of NZUs over the past 2 years:

The price for an NZU increased from around $22/tonne in early 2020 to around $68.50/tonne on Christmas Eve last year. Carbon farmers in New Zealand are now earning three times what they were earning for their NZUs two years ago. What other industry can point to such growth? If you’re a farmer and you’re interested in carbon farming, see for example here and here. I know of at least one farmer up in Tarras who is achieving excellent returns from carbon farming. Perhaps you should also be aware that research by the Ministry for Primary Industries in September last year assessed that there were about 380,000 hectares of eligible forest land across New Zealand that weren’t registered in the ETS. If 10% of that area was retained as permanent forest, that alone would generate NZUs worth more than $400 million (see here for more).

What if you’re not a farmer, can you participate in this market? Well, actually, yes you can. You can buy NZUs now and then sell them later to industries who need them to permit their carbon emissions. For those of you on Sharesies, the easiest way to do this is to buy shares in the Salt Funds Management Carbon Fund (SALT) which tracks the price of NZUs very closely. I note that today (31 Jan 2022) the 1-year price change on SALT shares on Sharesies is up 62.04%. Again, not a bad return on investment. But with a decreasing cap on government allocations of NZUs, and a carbon farming industry that appears to be unable to keep up with demand, my sense is that the price of NZUs is only going to increase. But that is not investment advice from me!

But that’s all a prelude to what I actually wanted to write about today. What does a ‘carbon farm’ look like? Well, pinus radiata as far as the eye can see. This prompts the following questions:

1. Is having large parts of our country covered in a monoculture, exotic tree species the price we wish to pay to achieve our Paris Agreement targets? and/or

2. Is paying people in other countries (a cash flux out of New Zealand) to plant trees to sequester the carbon emissions of New Zealanders the way we want to go?

First, it should be noted that most of the carbon plantations in New Zealand are foreign owned – one way or another we appear to be paying people in other counties to offset our domestic carbon emissions. And given the biodiversity crisis that New Zealand is facing, are forests of short-lived, highly flammable, pinus radiata trees the way to go?

My feeling is that it is not, and certainly not a path consistent with New Zealand’s aspirations as a tourist destination. Who will want to come to New Zealand to see vast forests of pine trees? When taking a short view, planting pinus radiata is preferable to planting native New Zealand trees as they are faster growing and generate more rapid returns in terms of NZUs produced. However, if a longer-term view is taken of the wide spectrum of co-benefits that would accrue from planting native tree species for carbon sequestration, and if those co-benefits could be appropriately priced into the New Zealand carbon market, this would likely lead to far better longer-term outcomes for New Zealand.

The good news is that there appears to be change on the horizon: while currently, for the purposes of the ETS, all indigenous tree species are lumped together, there are plans to redesign the ETS lookup tables to create new opportunities where faster growing native species will be recognised for greater rates of carbon sequestration. So here is a business model I would like to explore for some piece of land in Central Otago: plant 100 hectares of native forest now. This would earn around 760 NZUs/year on average between now and 2050. If sold at the current price of $68.50/NZU, that alone would generate an income of $52,060/year. But keep in mind that the value of an NZU tripled over the last 2 years. And given the expectation/promise that faster growing native species will soon be recognised for greater rates of carbon sequestration, we could soon be seeing returns of a couple of $100,000/year on a 100-hectare forest. Wait a few years for native bird species to inhabit the forest, build 10 glamping treehouses in the branches of some of the bigger trees, and charge $200/night for clients to sleep in those treehouses amongst the native birds. Assuming just 30% occupancy, that would generate another $220,000/year in income. I wonder if this could make for a viable tourism business?

Related Stories

-

Batteries and storing energy

“Nothing is more dangerous than an idea when it’s the only one we have” as Émile-Auguste Chartier once said. This quote springs to mind when I think of the Lake Onslow scheme. For those who may not know about the Lake Onslow scheme, the idea is to convert Lake Onslow, which sits in a shallow depression in the hills between Roxburgh and Middlemarch, into a giant battery. Importantly, Lake Onslow is around 685m above sea level while the Clutha River downstream from Roxburgh is at around 94m above sea level. That’s a 591m difference (see, those three years of maths at university are paying off).

Read more about Batteries and storing energy -

Extreme events and climate change

Consider the Paris Agreement where countries around the world have agreed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions with the goal of limiting global warming to well below 2°C, preferably to 1.5°C, compared to pre-industrial levels. Some people think “Who cares? It was 2°C warmer today than it was yesterday. 2°C is peanuts!”. Or consider sea-level rise. That could be around 3mm/year along the coast of Otago. That’s 3cm in a decade. Again peanuts, right? A wave could be 5 metres high so why are we worried about a 3cm rise over a decade?

Read more about Extreme events and climate change -

The Central Otago Destination Management Plan and Climate Change

CODC recently released its Destination Management Plan (DMP). I have read it and I think it’s excellent – and painful. Why painful? Because change is painful and this DMP highlights many changes to the way we do things that will be required. In this piece, I am going to share my thoughts on those aspects of the required changes articulated in the DMP that relate to climate change and are directly relevant to tourism services providers. Climate change poses an existential threat to some of the values that underpin the DMP, in particular Mauri - pressures imposed by land and water use are already being exacerbated by climate change and will be more so in the future.

Read more about The Central Otago Destination Management Plan and Climate Change -

Wood-burners and climate change

I often get asked about whether using wood-burners for interior heating contributes to climate change. For the purposes of this article, let’s set aside the effects that the use of wood-burners have on out-door air quality. Smoke from using wood-burners contributes to poor air quality; you only need to walk around Alexandra on a cold winter’s night with a strong inversion layer to notice that. But that’s mostly a different issue to climate change – I say ‘mostly’ because the aerosols (smoke) from wood-burners, if anything, make a small contribution to cooling the climate by reflecting solar radiation back to space before it reaches the ground.

Read more about Wood-burners and climate change